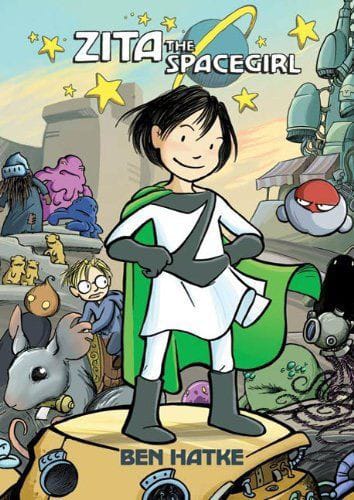

Ben Hatke’s Zita the Spacegirl (First Second, 2011) is often celebrated as a rollicking space adventure for middle-grade readers, but beneath its vibrant surface lies a nuanced exploration of imperfection, quiet courage, and the art of visual narrative. While most analyses focus on Zita’s heroism or the book’s whimsical world-building, few delve into Hatke’s deliberate subversion of traditional sci-fi tropes or the subtle interplay between innocence and consequence that defines the story.

1. The Aesthetic of “Soft Sci-Fi”

Hatke’s universe is a departure from the cold, sterile futurescapes of classic sci-fi. Instead, Zita offers a tactile, almost folksy cosmos filled with sentient pumpkins, neurotic robots, and crumbling alien markets. This “soft sci-fi” aesthetic—a blend of Kirby-esque dynamism and Studio Ghibli warmth—creates a world where danger coexists with charm. The crumbling Scriptorian Temple, for instance, is not just a set piece but a metaphor for Zita’s own fragmented resolve. Hatke’s watercolor-esque hues (muted blues, earthy ochres) soften the stakes without trivializing them, making the story accessible yet emotionally resonant.

2. Zita’s Imperfect Heroism

Zita is no invincible chosen one. Her defining trait isn’t bravery but curiosity—a quality that leads to both catastrophe and redemption. When she impulsively activates a alien device, stranding her friend Joseph in another dimension, Hatke frames her mistake not as a plot device but as a pivotal character moment. Unlike protagonists who stumble into heroism by accident, Zita actively grapples with guilt, a rarity in children’s comics. Her journey isn’t about embracing destiny but about learning to say, “I messed up, and I’ll fix it.”

3. Silent Panels, Loud Emotions

Hatke, a master of visual economy, uses wordless sequences to amplify tension. In one standout scene, Zita navigates a labyrinth of prison cells, her small figure dwarfed by oppressive shadows. The absence of dialogue forces readers to mirror her isolation, creating an intimate bond between character and audience. Similarly, the recurring motif of hands—Zita reaching out, Joseph’s fingers slipping from hers, Piper’s mechanical grip—communicates vulnerability and connection without a single speech bubble.

4. The “Un-Super” Supporting Cast

The crew Zita assembles—a neurodivergent giant (Strong-Strong), a guilt-ridden warrior (Mouse), and a disgraced android (Randy)—defy sidekick stereotypes. Each carries invisible scars: Randy’s self-deprecating humor masks existential dread, while Mouse’s stoicism hides grief over a fallen civilization. Even the “villains” lack mustache-twirling malice; the asteroid-headed Screed is less evil than exploitative, a commentary on capitalism’s cosmic reach.

5. Legacy and Lost Opportunities

While Zita spawned two sequels, its standalone magic lies in its restraint. Hatke resists overexplaining lore—Scriptorians’ origins remain mysterious, the “Device Universe” undefined—trusting young readers to embrace ambiguity. Yet, the series’ acclaim often overshadows its thematic depth. Critics praise its “girl power” messaging but overlook its quieter lessons: that saving the world doesn’t require superstrength, just stubborn empathy.

Conclusion: The Space Between Panels

Zita the Spacegirl endures not because it’s grand, but because it’s granular. Hatke’s genius lies in the gaps—the unspoken fears in Zita’s eyes, the way a single panel of Joseph’s abandoned sweater can evoke galaxies of loneliness. In an era of bombastic blockbusters, this graphic novel is a reminder that the smallest heroes (and the quietest stories) often shine brightest